Blow Up! The growth of things – works explained

Like a rhizome, a widely branching root system, the exhibition Blow Up! is permeated by the most diverse themes of our time, which, in the broadest sense, deal with the growth of things. In a variety of ways, the new works in the collection negotiate, explore, critique, caricature, and satirize traditional notions of growth. The focus is on the temporal and spatial dimensions of growth. However, with an impressive addition of more than eighty recent donations, the exhibition also focuses on the growth of the museum’s collection itself.

In the exhibition, two different concepts of growth repeatedly intersect: organic and cultural growth. Symbolic of these two tendencies is Phyllida Barlow’s Blob at the beginning of the exhibition, a “single-celled organism” that inflates into space and stands for the organic and evolutionary aspects of growth. In contrast, the video Remembering Paralinguay by Gary Hill refers to a cultural evolution of humankind. The video first returns perception to a zero point in the darkness before a woman strides out of nowhere toward the visitors. Her powerfully shouted sounds suggest a pre-linguistic or even future form of communication.

The unfolding of different forms of space and its exploration are the focus of the photographic series that follow: Also in darkness, Daniel Boudinet stages different spatial situations within his Parisian apartment at night. His images are the result of a technical play with light and shadow, as well as with transparencies, which is why he is considered one of the early pioneers of artistic color photography. The specific blue-green light immerses the furnishings and the rooms with their openings in a mysterious and at times eerie atmosphere.

The contrasting play of (architectural) distance and (intimate) proximity, privacy and public space is also continued by Alain Fleischer with his photomontages. He attempts to reverse the voyeuristic activity of photography and turn it into an exhibitionistic activity by projecting pornographic images onto the surrounding façades.

Adam Putnam explores the different qualities and perceptions of (inter)spaces. Influenced by the eighteenth-century architectural fantasies of Giovanni Battista Piranesi, he is especially interested in the psychological qualities and perceptions, as well as in spatial geometry and perspective illusion. On the one hand, he relates individual isolated architectural fragments and objects within his abstract photography to the abstract surrounding space. On the other hand, he forces his own body into direct physical interaction with the space in between by pressing himself into bookshelves and cupboards.

Based on his interest in the intangible, as well as in subconscious connections, with Zweisamkeitsimaginierung (Imagination of Togetherness), Jürgen Klauke also negotiates the relationship between the subject and the material world. In his stagings of psychologically highly charged situations, the human being becomes a mere prop. While in the first tableau vivant, the artist exposes himself to the leaden gravitational field, in the two following images, his presence is lost in a phantom-like state. The tables, balloons, bowls, and pillows form their own metaphysical reality and thereby push the existential question regarding the location of the subject to the fore.

Many of Stefan Thiel’s paper cut-outs are based on photographs he took in the urban context of Berlin. What interests him about the cut-out or silhouette, with its long cultural history, is the possibility of formal reduction of space and object. At the same time, the medium establishes a distance to what is depicted. As in the cut-out, various themes overlap in his works. The idea of sensuality and desire is one of his basic motifs. Despite his exploration of sexuality, eroticism, and fetish, especially within queer communities, his works occasionally obscure more than they actually reveal. This is also true of the photographic series Silhouetten, which depict people from his environment with black stockings pulled over their heads.

Concealing, even covering up or repressing, is part of US American (colonial) history and has played a key role in this up to the present day. A black-painted but badly battered plaster bust of a white man with a necktie has landed on the floor, standing in front of a large ensemble of paint buckets piled into leaning columns. The African American artist Rodney McMillian has linked the nameless bust as a found object to an allusion to the US American preference for the neoclassical architectural element of the column.

In contrast, the archetype of US American architecture, the white man’s log cabin, is the focus of Olga Koumoundouros’s sculpture Sagamore: The Good Life. “Sagamore” was the name given to the leaders of extended families of the Indigenous North American Abenaki. The log cabin architecture here has a closed form: Without windows or doors and with sides of equal size, it appears hermetic and forbidding as a poignant version of a self-sufficient dwelling. In this context, the title of Johannes Wohnseifer’s wall work, which refers to the United States, serves as a biting commentary by questioning the legacy of Western colonialism: not a flag not even a map. It contrasts with Goran Tomcic’s interpretation of the American flag, which he designed as a hologram collage.

With her series LA Gun Club, Olga Koumoundouros takes aim at the gun enthusiasm deeply rooted in American society: At three shooting ranges in Los Angeles, she used almost all commercially available firearms to shoot at pieces of Kevlar, a material that is considered bulletproof, and marked the bullet holes with the names of the gun models. It becomes apparent that this material is not at all as invulnerable as one has always claimed it to be. Due to the increasing number of killing sprees in the US-American civil society, this work has an explosive topicality.

Olga Koumoundouros’s Economic Recovery is a vehicle characterized by two brand-new SUV tires and a sports jersey stretched over a light metal frame. These elements of the ostentatious way of life are countered by the fabric element at the rear end, reminiscent of empty scrotums, on which the stoppers of a walking aid are also mounted.

Some thirty 30 years earlier, Fred Lonidier photographed the arrests of twenty-nine demonstrators in San Diego. They had been peacefully demonstrating against the Vietnam War and were then arrested and submitted to “criminal identification” before being loaded onto a police bus. Most of them were students. Lonidier, himself a student, stood right next to or behind the police photographer. Many of the photographs are characterized by a mood among the arrestees, as well as among some of the police officers, that is reminiscent of a grotesque Happening. Between the years 1961 and 1975, some 58,000 US-American soldiers and well over 1.2 million Vietnamese people died in the Vietnam War.

The activist artist Tejal Shah has taken found, hand-colored, and digitally retouched photographs from the flood of media images to give an idea of civilian casualties from the last sixty years. Among them is a Buddhist monk who burned himself to death as the most radical form of political protest against China’s brutal oppression of Tibet. Within the series, the artist shows in particular the lifeless bodies of boat refugees, thereby revealing the failure of border crossings as a result of flight and migration. The floating staging lends expression to the state of unbecoming.

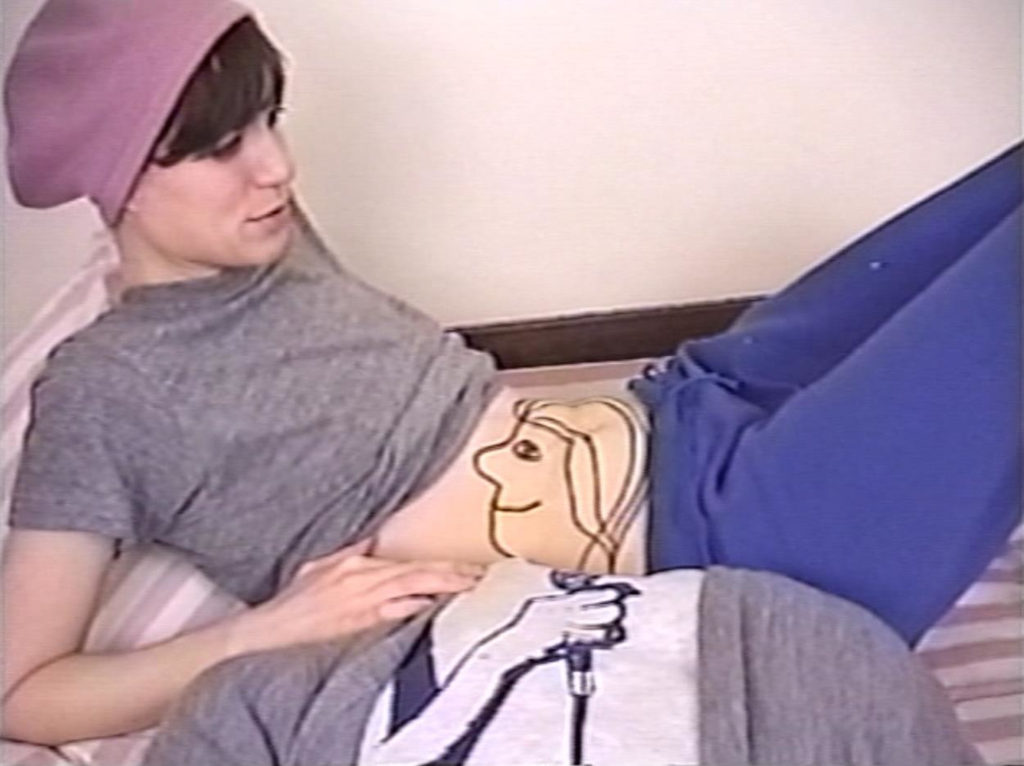

In the late 1990s, the feminist artist Wynne Greenwood founded the multimedia band Tracy + The Plastics as its only real member, embodying all the other fictional members herself. Working between different disciplines and in the tension between prescribed actions and free improvisation continues in the installation Peas (2007). Here, the artist enters into a direct dialogue with something physically absent. In this case, her anxiety-driven belly and her self-contrived worries engage in an argument. Greenwood repeatedly employs the medium of drawing in a targeted manner to visualize invisible forces, such as her own fears. As is clear from the superficial and rhetorical dialogue with an accusatory undertone, the drawn “pea faces” are caricatures of bourgeois viewpoints. The childlike representations contrast with the “adult” issues of power and representation, which are discussed here on a second level.

The painter Mariela Scafati continually expands the boundaries of her discipline by assembling canvases into moving bodies. The spatial relationships, as well as the demarcation of the canvases from one another—for example, in the form of the individual color shades and intensities—reflect the idea of social structures in an abstract way. The artist orchestrates her canvases via ropes, perceiving them as extensions of her own body. The rope technique itself is borrowed from the art of shibari, a Japanese bondage tradition, the erotic potential of which is used to find aesthetic body poses in space.

On the way to the next room, one passes the early video work Rock City Road, created in Woodstock, New York by the video pioneer Gary Hill. The work contains multiple layers of images of walking on various surfaces, including a sidewalk and a snow-covered terrain. The images were captured and edited using video recorders. The editing processes—fast forward, rewind, pause, and “scratching” through and between images—remain present, as do the sounds they produce. These noises function as a metaphorical link between the materiality of the world and the electronic media.

With his impressive pneumatic ensemble Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil, 1969)—among the first of his so-called “Inflatables”—Otto Piene reveals most clearly the reciprocal relationship between growth and decay. The title is borrowed from Charles Baudelaire’s eponymous book of poetry, written in the mid-nineteenth century. The play with natural forces and elements also continues in Piene’s ceramic works, which he himself described as his “heavy paintings.” For Piene, all elements—light, air, water, and fire—intertwine in this medium. He is particularly interested in the play of light, which results from the refraction of light on the broken surface of the reliefs, as well as from the application of the glazes.

Piene’s wall works in clay enter into a dialogue with the “whipped” ceramic pictures by K. O. Götz. What both artists have in common is that they only found their way to working with clay at an advanced age and realized their wall reliefs in the same workshop in Cologne. The painter—teacher of Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke, and Franz Erhard Walther, among others—of the Art Informel that developed in Europe from the 1940s onwards, and who is best known for his use of squeegees, describes the result as “an exploration of the material, in the way I can drive it forward.” The intractability of the tough material prompted him to shape the mass at times using his entire body. For Götz, the spontaneous and gestural aspect of Art Informel lay in the furious beating around himself.

In both photography and film, blow-up is also understood as the technical possibility of enlargement. Jochen Lempert, a biologist by training, is also a master of playing with size. His analog black-and-white photographs stand out sensually due to their coarseness and thus develop a proximity to the medium of drawing. From the field of natural science, he transfers the method of classification to his own artistic practice. By pursuing aesthetic criteria in collecting, archiving, evaluating, and compiling his motifs, however, he undermines thinking in terms of strict classifications. The animals portrayed frontally are either living or already extinct species, as well as effigies of them. Characteristic of the works is that, despite the documentary approach, the animals display humanized features.

The black-and-white film I’m sorry but I don’t want to be an Emperor… by Jordan Wolfson features a man without a head who communicates emotionally in sign language. The title refers to Charlie Chaplin’s speech at the end of the satirical film The Great Dictator (1940). Wolfson translated this speech into the soundless gestures of sign language, accompanied by the rattling of a 16mm projector. In doing so, he allows Chaplin to return to his original channel of communication: silent film. By placing the figure in front of a sterile white background, Wolfson drew inspiration from the Danish artist Jørgen Leth’s short film The Perfect Human (1967), which deals with the impossibility of human perfection. By bringing these two extremes together, Wolfson positions Chaplin’s idealism alongside a nihilistic view. At the same time, with this juxtaposition, he reflects on the futility of human action and despair, as well as on values and ideals in times of political oppression.

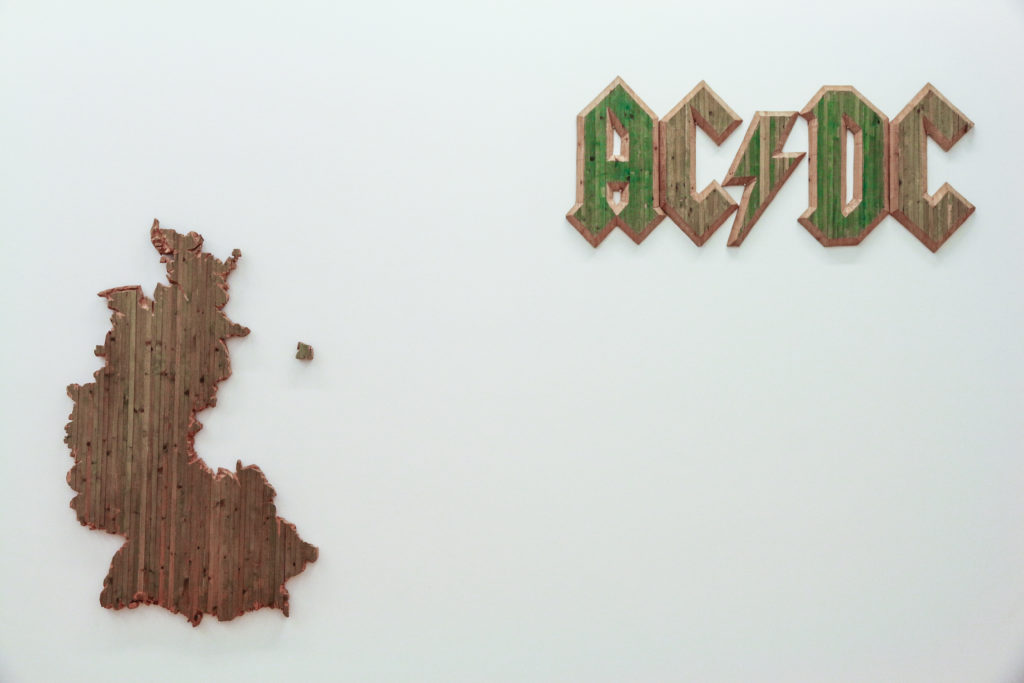

Ten years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, René Lück’s wall relief BRD addresses the division of Germany and, with this, the competition between two political systems. The term AC/DC (alternating current / direct current) had been taken up by the famous Australian rock group in 1973 and appropriated as its name. “René Lück is an archaeologist of collective memory. With his installations, he uncovers hidden images and symbols concealed in the deeper layers of our social memory and brings them to the center of our attention. Lück turns primarily to objects and representations that are considered symbols of political self-determination and have thus become icons of collective memory.” (Michael Dethleffsen) The theme of collective memory is also taken up by Goran Tomcic with his Baby Blue Flag, commemorating the people who contracted HIV and fell ill due to AIDS in the United States in the 1980s.

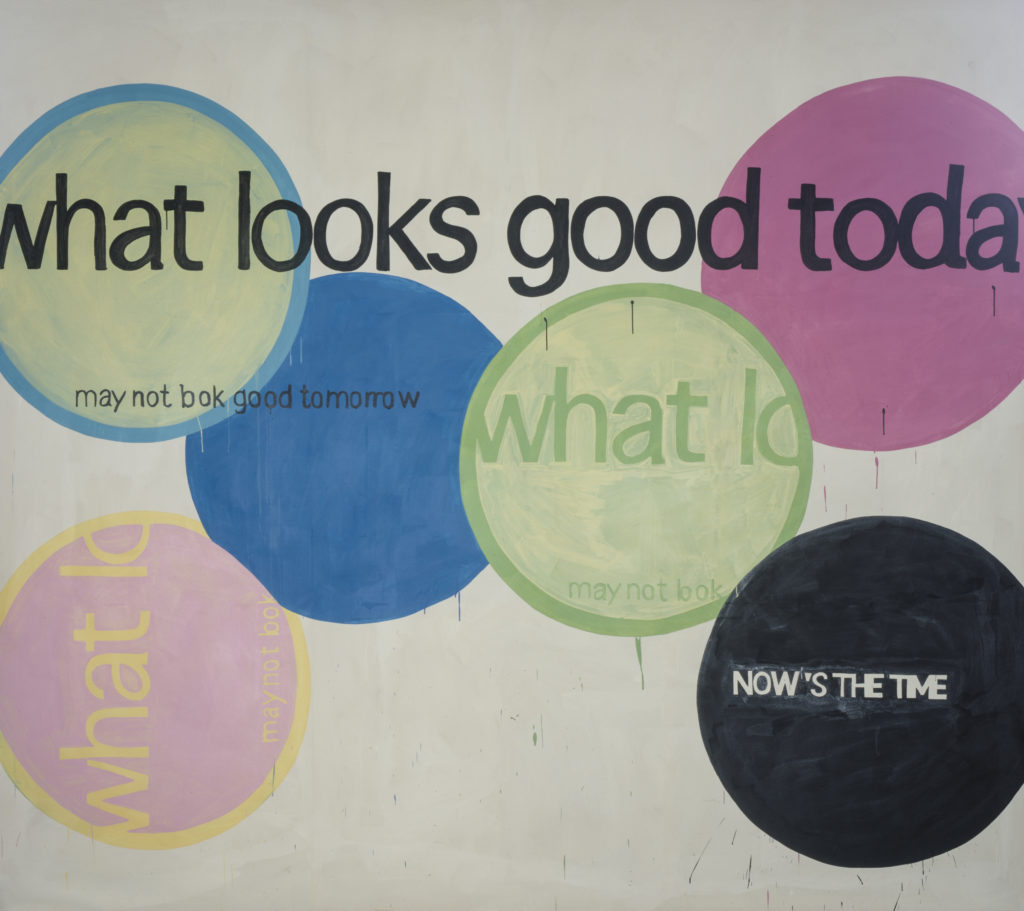

Also touching on the theme of historical developments is the title of the large-format painting What looks good today may not look good tomorrow by Michel Majerus. Here, the work serves to commemorate the artist who died in a plane crash on November 6, 2002 [see wall text].

What is central to all these works is, more than anything else, the search for orientation, a need that is perceived with increasing intensity in the age of globalization. Mapping the unmappable is what Nathan Carter attempts to do with his wall reliefs in a deliberately naïve aesthetic, in order to point to invisible communication systems and mobility structures in the urban context. As an artist, he uses his reliefs to question the drawing of territorial boundaries.

At the beginning of the exhibition, one can experience how movement, action, and the search for meaningfulness develop out of the black depth of space—virtually from nothing. This search for meaningfulness is taken up by the exhibits in numerous ways and comes to a head towards the end of the exhibition: Johannes Wohnseifer lets us step in front of a white picture covered with a real camouflage net and thus hidden from our gaze, the picture thus rigorously denied to our vision.

Also at the end of the exhibition, a “material bubble” by Phyllida Barlow hangs from the ceiling, similar to the one at the beginning of the exhibition, but now much larger and more threatening and mutated into a kind of multifocal surveillance camera: Under it, one finally leaves the exhibition with the feeling of being oneself observed or even monitored.

All new acquisitions are thanks to generous collectors and artists, to whom we would like to express our sincere gratitude for the works of art they have donated and for their extraordinary commitment.

Acrylfarbe, leere Farbdosen, gefundene Gipsbüste), Gesamtmaß

variabel, © Rodney McMillian, courtesy der Künstler und Vielmetter

Los Angeles, Foto: Gene Ogami, Schenkung aus Privatsammlung

San Diego (Detail), 1972, 29 Schwarzweißfotografien und ein Deckblatt, Ed. 2/3, je 12,8 x 20,3 cm,

Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, Schenkung Privatsammlung, Berlin, © Fred Lonidier

Acryl auf Leinwand, © Michel Majerus, Foto: Marek Kruszewski

Holz ca. 180 x 180 x 180 cm, Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg Schenkung aus Privatsammlung,

© Phyllida Barlow, Foto: Marek Kruszewski